- Published on

Lock Free Queues In C++

- Authors

- Name

- Ritu Raj

- @rituraj12797

Last 2 months, I spent most of my time exploring deep OS internals and working on a low-latency project in C++. It involved some of the most interesting applications of OS and COA (Computer Organization and Architecture) concepts I studied back in my sophomore year. To be honest, I was flabbergasted and humbled by the engineering marvel computer scientists and engineers achieved in designing Operating Systems, CPUs, general computer architecture, and the G.O.A.T: C++.

Though there are many things I could discuss at length here, for today's blog, I will talk mostly about a certain component which I found super interesting: a Lock-Free medium of communication between two threads.

So here's how the story started. A part of my ongoing project is a communication channel—basically a mechanism for two concurrent processes to communicate through. It is similar to a channel (if you also did Go-lang you will relate to this) or Pipes (a general OS term), but since the project is heavily focused on performance, it needs to be extremely fast.

Initially, I started off with a very naive approach of using a normal queue with mutex locks. Though it worked well, this turned out to be disastrous in terms of performance. The issue with this approach is that it uses mutex locks which are provided by the OS, and when they are contended, their acquiring latency goes extremely high (10 to 20 microseconds, which is approximately 40,000 to 100,000 CPU cycles). Such terrible performance is very costly, so I needed to optimize that.

Then I thought of using a spin lock (A Good Stack-Overflow Discussion On Spin Locks) here. Although it worked and provided lower latency, it resulted in CPU hogging due to continuously checking on the availability (an analogy for this would be polling).

After some research (read this awesome research paper from the Pittsburgh website: Implementing Lock-Free Queues), I found out about Lock-Free Queues. These provided a promising way of implementing a mechanism that would provide synchronization for two threads to communicate, with no locking and no CPU hogging.

The paper discussed a linked list-based approach, but modern implementations of lock-free queues are done mostly using ring buffers (which I earlier thought to be a very complex data structure, to be honest), and this is how I finally decided to implement one.

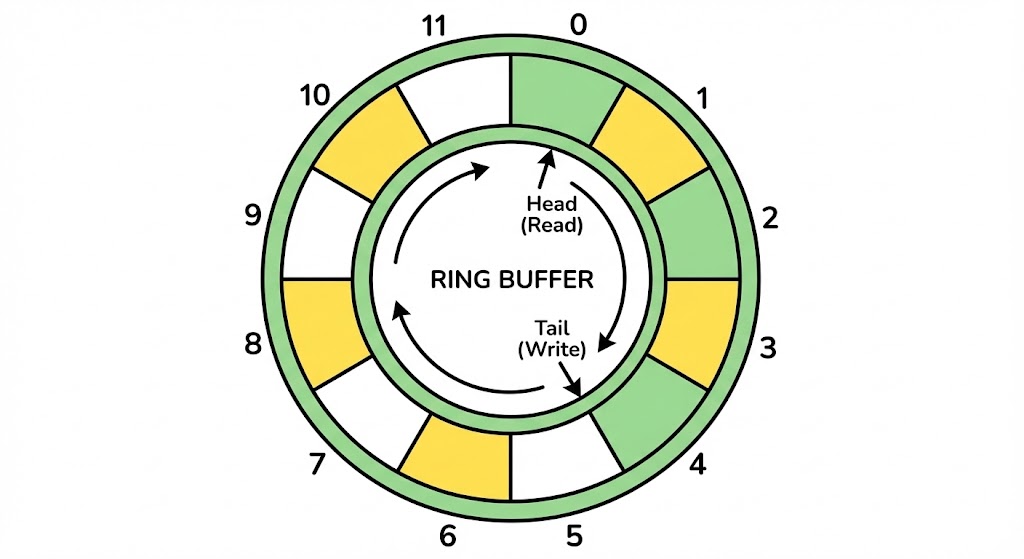

1. But What is a Ring Buffer and what does it look like?

A Ring Buffer is nothing but a data structure formed by connecting the end of an array to its start in a structure that looks like a ring hence a ring buffer.

That's it, simple and easy.

When you iterate on it, it goes like 0, 1, 2, 3, 4... n-1, 0, 1, 2... and so on. The iterator keeps on rotating and wrapping between 0 and n-1.

2. How is it going to help us implement a queue?

This is where it gets interesting. You might be familiar with a technique called "2 pointer"; that is exactly what we use here. We maintain 2 pointers, one for the read and one for the write.

- Read Pointer (we name it

next_index_to_read_from): It points to the index of the buffer from where we should read the Data. To be precise, it represents our front element of the queue. - Write Pointer (which we write here as

next_index_to_write): It points to the next index where we will write the data (the index which will keep the last data,queue.back()).

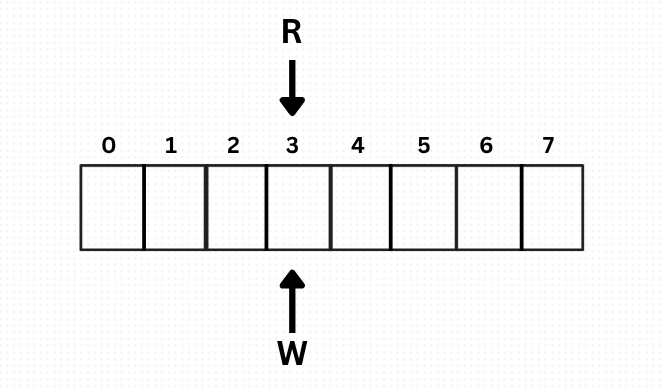

3. What does it look like Initially?

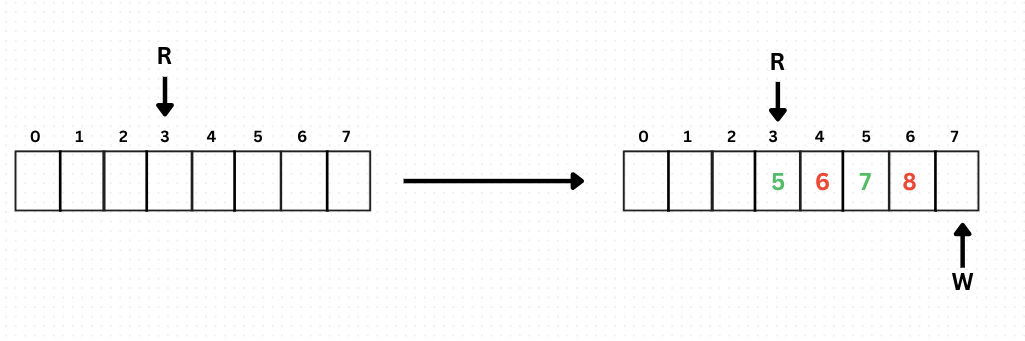

Initially the buffer is all empty and the read head R and write head W both point to same index.

4. How does Write work here?

The way writing works here is to simply write the data to wherever the writer head is pointing to and move the writer head (as simple as that). But there is a twist here, which we will look at through an example.

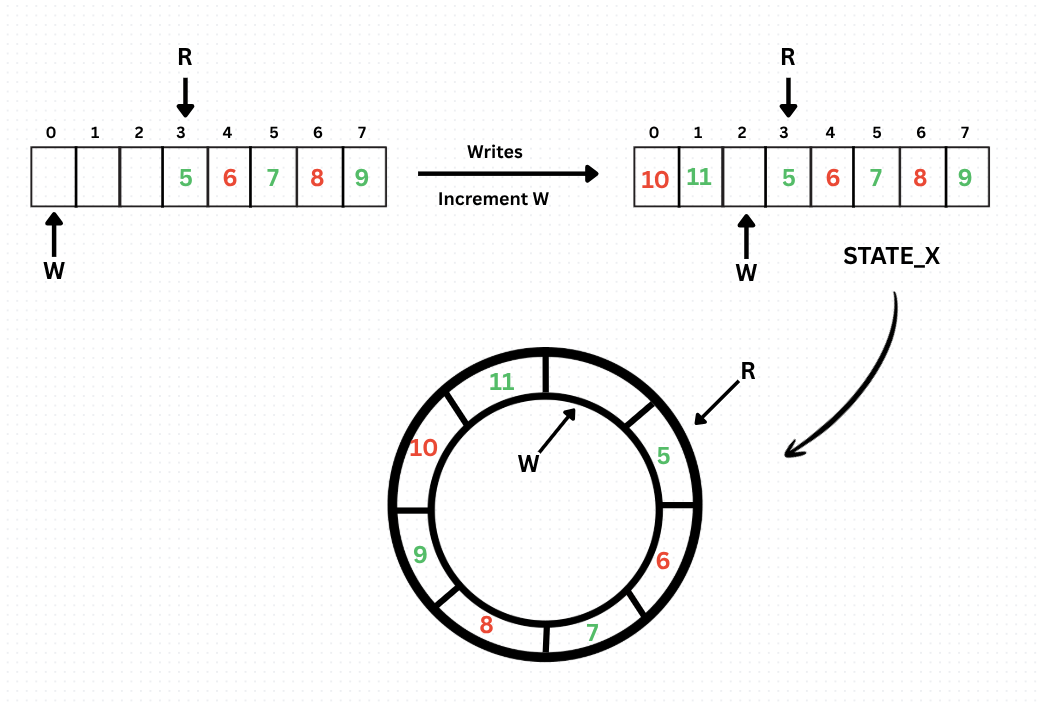

Now we are at the end, so when a new write comes, we will write the data at this index and wrap the Write head to the start of the array. More formally, we are incrementing the Write head as:

WRITE = (WRITE + 1)%ARR.size();

Now there will be a state where we will be left with a single slot to write to, and just after that, there will be the Read head (it has not moved since we have not read anything yet). We name this state State X (we will need it later).

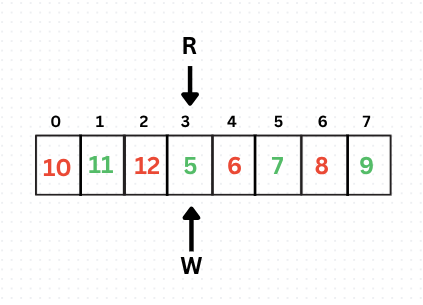

Now say the writer writes the last entry too, and the queue is full and looks something like this:

Now the queue is full, but wait, did you notice something?

The complete queue state and the empty queue state create confusion, don't they? If you notice, the Reader and Writer head pointed to the same index when the array was empty initially, and in the final complete state, they also refer to the same index when the queue is full.

So R = W will imply Complete state or Empty State?

Interesting, right? Well, there is a very simple approach to tackle this. Remember State X? We will denote it as the full state (i.e., when write is just 1 behind the read head, we will consider the queue to be full), and the writer won't be allowed to write anymore until the reader reads something.

Now we have proper identifiers:

- When

R = W, we say the queue is empty. - When

(Write + 1) % size = Read(when the next index, which will be the updated one, coincides with the read head), we say the queue is full, sacrificing one slot.

This technique is literally used in the Lock-Free Ring Buffer's implementation inside the Linux Kernel. Though I don't know the standard name for this, I call it the Sacrificial Slot Technique.

This means when we arrive at State X ((write + 1) % size = read), we will stop writing until the reader reads something.

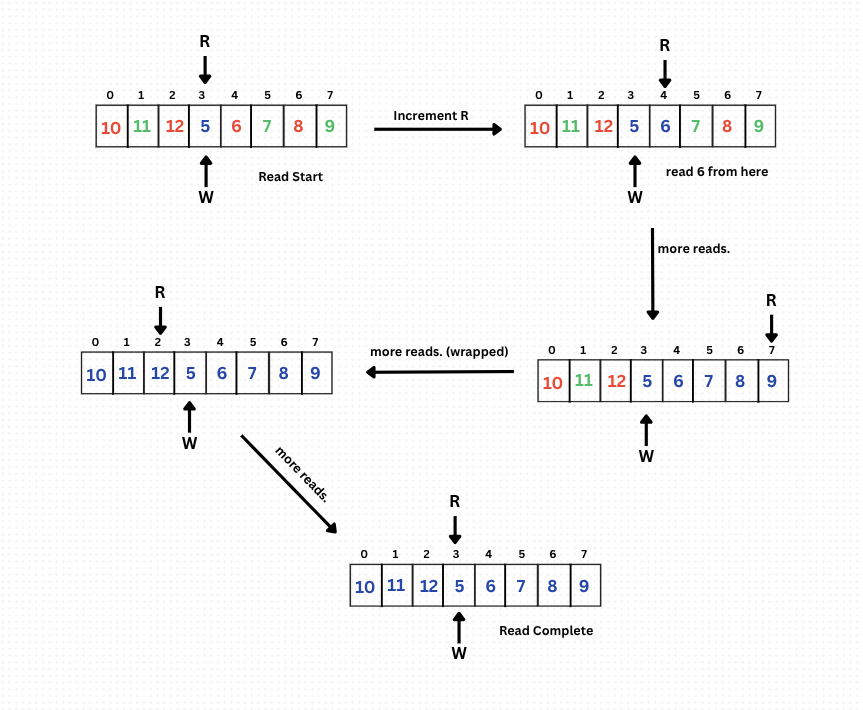

5. Now how does the Read Happen?

This is very simple; there is no complexity here.

First and foremost, we have a check here: if reader == writer, then we won't read anything and wait. Why? Because the write index refers to the location where we will put our data next (it is not there yet), and the read index means the data we will read from. How can we read from the place where there is no data yet?

Other than this scenario, we will do the same here: keep reading and incrementing R in the manner R = (R + 1) % size. This maintains the FIFO property, effectively simulating a queue. Similarly, this also wraps around, and this also reads until the following state:

When the reader reads this last entry and increments, we arrive at State R = W, meaning we consumed all the data that was available, and now before reading next, we should wait for the writer to write something.

This is how Ring Buffers work. One more thing which is interesting to note here is that after we read data, we need not clear it or delete it; we can simply overwrite it while writing as the value is of no use now.

6. One doubt which I faced and you should also have thought about by now

In practical scenarios, a queue is never of a fixed size, then why are we using a fixed-size queue here?

Well, that is because allocating memory dynamically at runtime is very costly in terms of time (heap scans cause a lot of trouble). So what we do is we find an estimate of the maximum number of elements that would be there in the queue at any point in time in the worst scenario of our use case. Say this number is X; then we keep a size usually in multiples of X. It is recommended to use 100X or 50X to accommodate spikes and extreme cases easily. This provides speed and ensures working in most cases.

7. Now to the Synchronization part

How do we synchronize access to the shared resource?

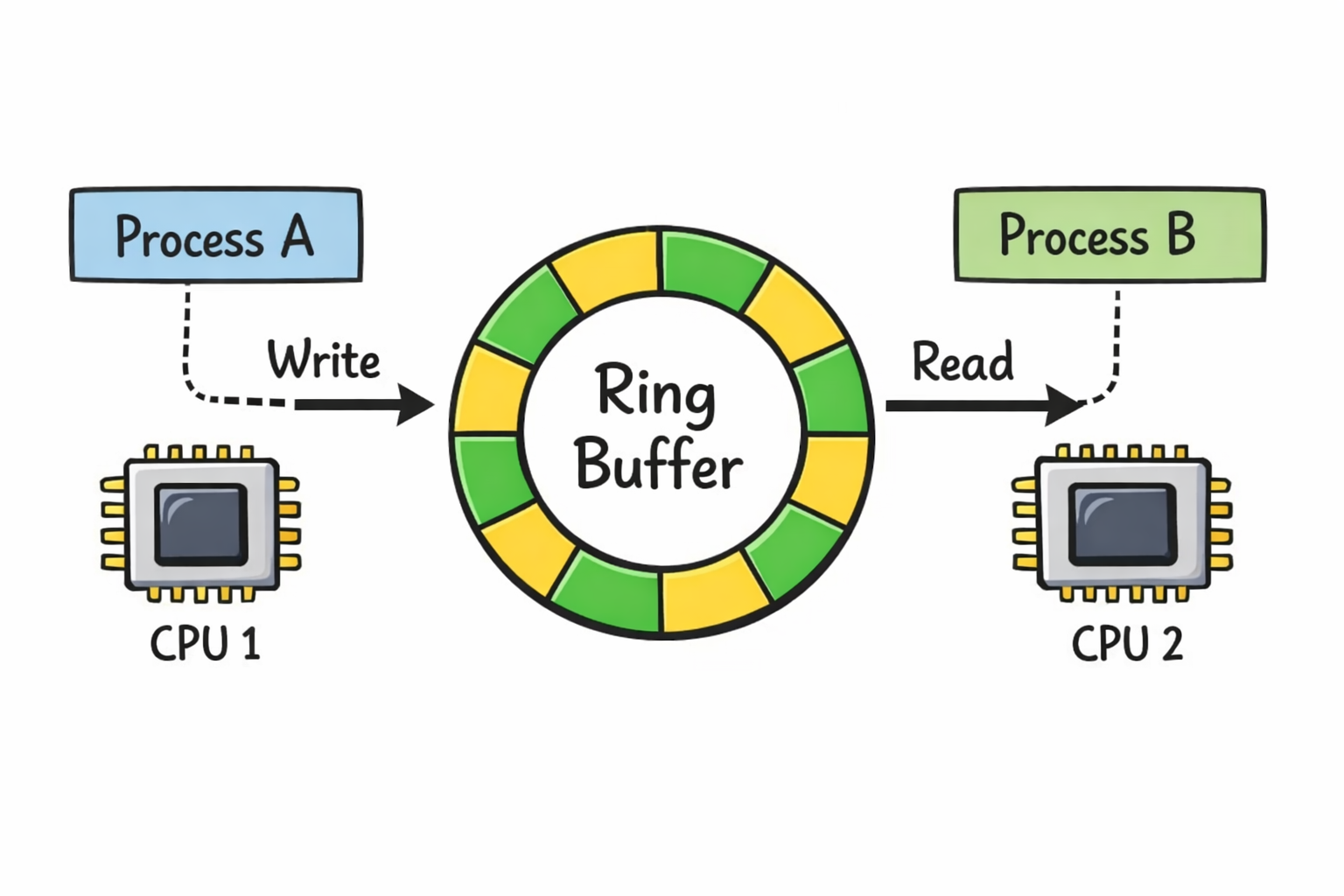

This is the most critical part of the system. Before we throw code at the problem, we need to understand the architecture of our communication.

My project specifically needed an IPC mechanism for communication between two threads working on different cores. This gives us a very specific constraint: we have One Process that ONLY writes and One Process that ONLY reads.

This is classically known as the SPSC Problem (Single Producer Single Consumer).

Why is this important? Recognizing that we are in an SPSC scenario is the key to optimization. If we had multiple writers (MPMC), they would fight each other to grab the "write head," forcing us to use heavy synchronization. But since we have only one writer, we might be able to get away with something clever.

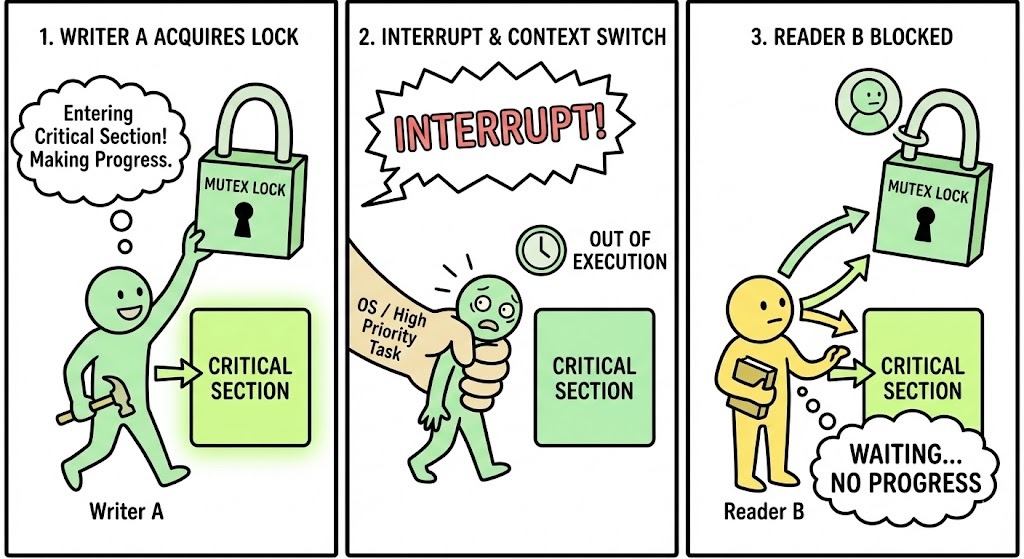

The "Standard" Mutex Approach (and why it fails) Let's go back to Mutexes for a moment to see why they fail, even in this simple one-on-one scenario. I believe buildups are necessary to appreciate the solution, so bear with me.

Consider we use a shared variable (like std::queue with a std::mutex) protected by a lock.

- Writer A arrives to write data.

- Writer A acquires the mutex Lock and enters the critical section.

- Suddenly, the OS scheduler interrupts! A high-priority task needs the CPU.

- Context Switch: The OS pauses Writer A. It is now asleep, holding the lock.

- Writer A is making no progress.

- Reader B arrives. It tries to read, but it sees the lock is held (by the sleeping Writer A).

- Reader B is forced to wait. It cannot read, even though the CPU might be free for it.

This is what we call a BLOCKED state. Even though Reader B was ready to work, it was stopped because Writer A was asleep. This dependency kills latency. Mutex locks cannot prevent this.

So, we define something called "Non-Blocking Synchronization Mechanisms". This primarily consists of 2 types: Lock-Free and Wait-Free algorithms. (I could continue discussing these here, but the blog will become large; let's save this one for later ;) ).

So we will focus majorly on Lock-Free algorithms here.

8. What exactly is a Lock-Free mechanism?

It is a way of implementing synchronization such that it guarantees at least one thread is making useful progress at any given time.

Think about the Mutex scenario above: both threads were stuck (one sleeping, one waiting). In a Lock-Free system, that never happens. If one thread is asleep, the other thread can still do its job.

- Blocking: "I cannot work until you are done."

- Lock-Free: "I can work even if you are slow/asleep."

In practice, we often use retry loops with atomic instructions (Fetch_and_Add, compare_and_exchange) for this. Here is a great video on Lock-Free and Wait-Free mechanisms which may help you: (Lock-free vs. Wait-free)

9. How is our queue Lock-Free then? (The Benefits Of SPSC)

Now, let's peel back the layers of the onion and connect everything. We established two things:

- We have a Single Producer Single Consumer (SPSC) setup.

- We want to avoid locks to prevent blocking.

The Nature Of Our Queue Our queue is Lock-Free because we essentially "split" the shared data ownership.

WAIT WHAT??? "Aren't we sharing the buffer?" you ask. "How can it be lock-free?"

Yes, the buffer memory is shared. But to make the queue thread-safe, we don't lock the buffer; we manage the pointers.

Look closely at our Ring Buffer again:

- We have a Read Head (

R). - We have a Write Head (

W).

The Ownership Model: In our SPSC scenario, we enforce a strict rule:

- Only the Reader is allowed to modify

R. The Writer only looks at it. - Only the Writer is allowed to modify

W. The Reader only looks at it.

But wait, don't we need a lock to read safely? You might be getting a vibe here: 'If the Reader is modifying R and the Writer tries to read R at the exact same moment, won't that cause a crash or garbage value?'

This is a very normal concurrency doubt (I also got conused here). In normal C++, reading and writing a variable simultaneously causes a Data Race. But here, we use Atomics (std::atomic).

Because the hardware guarantees the update to atomic variables are atomic in nature (indivisible), The thread which will be reading will never see a garbage value.

Why this makes it Lock-Free: Since the Writer is the only thread in the entire universe that updates W, it will never collide with anyone else trying to update W. It doesn't need to lock W because it owns it!

Similarly, the Reader owns R. It updates R whenever it consumes data. It doesn't need to ask for permission.

The Result:

- Writer: "I want to write. I check

R(atomic load) to see if I have space. If yes, I write and updateW(atomic store)." - Reader: "I want to read. I check

W(atomic load) to see if there is data. If yes, I read and updateR(atomic store)."

No contention. No locks. No heavy OS Context Switches blocking the other thread. We have achieved Lock-Free synchronization simply by respecting the ownership of these two variables.

In fact, this design is technically Wait-Free (the strongest guarantee), because as long as the queue isn't full/empty, every operation completes in a constant number of steps. If we change the scenario to Multiple Producers (MPMC), our current code breaks immediately. If two writers try to increment next_index_to_write at the same time, they will overwrite each other's data (Data Race). To fix this without Mutexes, we have to use CAS (Compare-And-Swap) loops. This degrades the system from Wait-Free to Lock-Free.

10. Implementation

Below is my implementation of this queue with comments for details.

namespace internal_lib {

template<typename T>

class LFQueue final {

private :

std::vector<T> store_;

std::atomic<size_t> next_index_to_read = {0};

std::atomic<size_t> next_index_to_write = {0};

public :

explicit LFQueue(std::size_t capacity ) : store_(capacity, T()){

// initialize size here

// explicit used here to prevent any auto type conversion

}

// delete extra constructors

LFQueue() = delete;

LFQueue(const LFQueue&) = delete;

LFQueue(const LFQueue&&) = delete;

LFQueue& operator = (const LFQueue&) = delete;

LFQueue& operator = (const LFQueue&&) = delete;

auto getNextWriteIndex() noexcept {

// we see if the queue is full then return the nullptr

// an Important lesson here

return (((next_index_to_write + 1)%store_.size()) == next_index_to_read ? nullptr : &store_[next_index_to_write]);

}

auto updateWriteIndex() noexcept {

// no contention here as our queue is SPSC ==> single producer single consumer ==> only one writer, so only it will update the write index

internal_lib::ASSERT(((next_index_to_write + 1)%store_.size()) != next_index_to_read ," Queue full thread must wait before further writing");

next_index_to_write = (next_index_to_write + 1)%(store_.size());

// I know this is not a simple operation so it is not atomic but since we have a single writer no contention will happen here

}

auto getNextReadIndex() noexcept {

// if the consumer consumed all the values and is now pointing to the next write index ==> means the place to which it is pointing has no data yet so we return nullptr

return (next_index_to_read == next_index_to_write ? nullptr : &(store_[next_index_to_read]));

}

auto updateNextReadIndex() noexcept {

internal_lib::ASSERT(next_index_to_read != next_index_to_write," Nothing to consume by thread ");

next_index_to_read = (next_index_to_read + 1)%(store_.size());

}

};

}

11. Using LF_QUeue and Benchmarking

We have built the queue; now it is time to stress-test it.

Below is the complete benchmarking harness that puts our LFQueue against a standard std::queue protected by a std::mutex. I strongly encourage you to dissect this code line-by-line rather than just scrolling past it. How we measure nanosecond-level latency without introducing observer effect, and how we simulate "Backpressure" using std::this_thread::yield() will give you significantly deeper insights into how your software interacts with the hardware metal.

#include<iostream>

#include<vector>

#include<chrono>

#include<atomic>

#include<thread>

#include "lf_queue.h"

#include "imp_macros.h"

#include "thread_utils.h"

#include<new>

#include<queue>

#include<mutex>

#include<algorithm>

struct Order {

int stock_id;

int quantity;

bool buy;

Order(int id = 5, int number_of_stocks = 6, bool is_buy = false) {

stock_id = id;

quantity = number_of_stocks;

buy = is_buy;

}

};

void showBenchmark(std::string text, std::vector<std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano>>& write, std::vector<std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano>>& read ) {

std::sort(write.begin(),write.end());

std::sort(read.begin(),read.end());

int ind_fifty = write.size()/2;

int ind_nine_zero = (9*write.size())/(10);

int ind_ninty_nine = (99*write.size())/(100);

int ind_nine_nine_nine = (999*write.size())/(1000);

std::cout<<" ========================================= BENCHMARK PERFORMANCE FOR "<<text<<"================================ \n\n\n";

/* ======================= BENCHMARK RESULTS NOW =============================== */

std::cout<<" WRITE LATENCIES \n";

std::cout<<" P50 : "<<write[ind_fifty].count()<<"\n";

std::cout<<" P90 : "<<write[ind_nine_zero].count()<<"\n";

std::cout<<" P99 : "<<write[ind_ninty_nine].count()<<"\n";

std::cout<<" P99.9 : "<<write[ind_nine_nine_nine].count()<<"\n";

std::cout<<" READ LATENCIES \n";

std::cout<<" P50 : "<<read[ind_fifty].count()<<"\n";

std::cout<<" P90 : "<<read[ind_nine_zero].count()<<"\n";

std::cout<<" P99 : "<<read[ind_ninty_nine].count()<<"\n";

std::cout<<" P99.9 : "<<read[ind_nine_nine_nine].count()<<"\n\n";

std::cout<<"\n========================================================================================================\n\n\n";

}

int main() {

std::cout<<" Main Thread Executing \n";

int set_size = 1000000;

std::vector<Order> test_set(set_size, Order(5,6,false));

// ======================================= STD QUEUE + MUTEX LOCKS ==============================================

std::queue<Order> std_queue;

std::mutex mtx;

std::atomic<bool> done = {false};

std::vector<std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano>> write_times;

std::vector<std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano>> read_times;

// writer lambda

auto writer_f = [](std::queue<Order>& std_queue,std::vector<Order>& test_set, std::vector<std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano>>& write_times , std::mutex& mtx, std::atomic<bool>& done ) {

// write million entries with mutex locks

for(int i = 0 ; i < 1000000; i++) {

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

mtx.lock();

std_queue.push(test_set[i]);

mtx.unlock();

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano> interval = end - start;

write_times.push_back(interval);

}

done = true;

};

// reader lambda

auto reader_f = [](std::queue<Order>& std_queue, std::mutex& mtx, std::atomic<bool>& done, std::vector<std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano>>& read_times ) {

int rc = 0;

while (true) { // Loop forever until we explicitly break

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

mtx.lock();

if (std_queue.empty()) {

mtx.unlock();

// If queue is empty AND writer is finished, we can stop.

if (done) break;

// Otherwise, writer is still working, so we yield and wait for data

std::this_thread::yield();

continue;

}

// If we are here, queue has data

Order entry = std_queue.front();

std_queue.pop();

rc += (entry.stock_id > 0 ? 1 : 0);

mtx.unlock();

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano> interval = end - start;

read_times.push_back(interval);

}

};

// writer thread

auto writer_thread = internal_lib::createAndStartThread(3," std writer ", writer_f, std::ref(std_queue), std::ref(test_set), std::ref(write_times), std::ref(mtx), std::ref(done));

// reader thread

auto reader_thread = internal_lib::createAndStartThread(4," std reader ", reader_f, std::ref(std_queue), std::ref(mtx), std::ref(done), std::ref(read_times));

if(writer_thread != nullptr) {

writer_thread->join();

}

if(reader_thread != nullptr) {

reader_thread->join();

}

showBenchmark(" std::queue + mutex ",write_times, read_times);

// ======================================================== LOCK FREE QUEUE ========================================

internal_lib::LFQueue<Order> ring_buffer(50000000); // 50 x 1M

std::vector<std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano>> lfq_write_times;

std::vector<std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano>> lfq_read_times;

// write lambda

auto wf = [](internal_lib::LFQueue<Order>& comm, std::vector<std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano>>& lfq_write_times) {

int cnt = 0; // I Million Orders

while(cnt < 1000000) {

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto write_ptr = comm.getNextWriteIndex();

while(write_ptr == nullptr) {

std::this_thread::yield();

write_ptr = comm.getNextWriteIndex();

}

*write_ptr = Order(cnt, 100, true);

comm.updateWriteIndex();

cnt++;

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano> interval = end - start;

lfq_write_times.push_back(interval);

}

};

// read lambda

auto rf = [](internal_lib::LFQueue<Order>& comm, std::vector<std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano>>& lfq_read_times) {

int cnt = 0;

while(cnt < 1000000) {

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto* read_ptr = comm.getNextReadIndex();

while(read_ptr == nullptr) {

std::this_thread::yield();

read_ptr = comm.getNextReadIndex();

}

comm.updateNextReadIndex();

cnt++;

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double,std::nano> interval = end - start;

lfq_read_times.push_back(interval);

}

};

// writer thread to lf_queue

auto wt = internal_lib::createAndStartThread(6," writer to lq_queue ",wf,std::ref(ring_buffer),std::ref(lfq_write_times));

// reader thread

auto rt = internal_lib::createAndStartThread(5," writer to lq_queue ",rf,std::ref(ring_buffer),std::ref(lfq_read_times));

if(wt != nullptr) {

wt->join();

}

if(rt != nullptr) {

rt->join();

}

showBenchmark(" LF_queue ",lfq_write_times, lfq_read_times);

return 0;

}

12. Benchmark results and Analysis

Following the implementation, I benchmarked this Lock-Free Queue against a standard std::queue protected by a std::mutex. I ran 100 iterations, pushing and popping 1 million integers in each run, to measure the latency distribution.

The Data

Below is the summary of average latencies across 100 million operations.

| Metric | Mutex Queue (ns) | Lock-Free Queue (ns) | Verdict |

|---|---|---|---|

| P50 (Median) | ~61 | ~77 | Comparable / Nearly Equal |

| P90 | 266 | 107 | LFQ is 2.5x Faster |

| P99 | 554 | 126 | LFQ is 4.4x Faster |

| P99.9 (Tail) | 2,476 | 212 | LFQ is 11.6x Faster |

1. The P50 (Median) Analysis

Observation: At the median, the performance of both queues is nearly equal. Both implementations operate comfortably in the sub-100 nanosecond range.

Learning & Insights: While the Mutex appears slightly faster in some runs (due to CPU cache locality when uncontended), this difference is largely negligible. In a real-world OS environment, background noise and scheduling jitter often blur the lines at this granularity. Ideally, without these OS interruptions, the atomic instruction overhead of the Lock-Free queue is comparable to the uncontended mutex lock/unlock cycle. Effectively, at P50, they are in the same weight class.

2. The P90 Analysis

Observation: The separation begins here. The Mutex latency drifts up to 266ns, while the Lock-Free queue remains rock steady at 107ns.

Learning & Insights: This is where the architecture starts to matter. Roughly 10% of the time, the Mutex encounters minor contention threads bumping into each other forcing a wait. The Lock-Free queue, however, ignores this "traffic" entirely, continuing to process data at near-constant speed.

3. The P99 Analysis

Observation: The gap widens significantly. The Mutex latency doubles again to 554ns, while the Lock-Free queue barely notices the pressure, sitting at 126ns.

Learning & Insights: At the 99th percentile, the Mutex version is 4.4x slower. The overhead of lock contention is now compounding. Meanwhile, the Lock-Free queue demonstrates incredible robustness; even under heavy load, it refuses to slow down, maintaining a variance of just ~20ns from its median.

4. The P99.9 (Tail) Analysis

Observation: This is the "Money Shot." The Mutex queue explodes to 2,476ns (2.4µs), while the Lock-Free queue holds the line at 212ns.

Learning & Insights: The Lock-Free queue is 11.6x faster in the worst-case scenario. The massive spike in the Mutex version happens because the OS Scheduler intervenes. When a lock is contested for too long, the OS puts the thread to sleep (Blocking). Waking it up takes microseconds. In contrast, the Lock-Free queue demonstrates its Wait-Free property here. It never sleeps, it never blocks, and it completes its task in a predictable number of CPU cycles regardless of what the other thread is doing.

Conclusion: Why Stability Matters

In Low Latency applications (like High-Frequency Trading, Real-Time Audio, or Gaming), Predictability Is Very Important.

You might look at the P50 and say they are similar, but the Tail Latency tells the true story.

- Mutex Window: 60ns to 3,000ns (High Variance / Unstable).

- Lock-Free Window: 90ns to 220ns (Tight / Predictable).

A system that is usually fast but occasionally freezes for 3 microseconds is dangerous—that is enough time for a market to crash or a frame to drop. A system that is consistently 200 nanoseconds, even on its absolute worst day, is superior. This benchmark proves that the Lock-Free implementation provides the nanosecond-level consistency required for critical systems.

14. Extras

As always I conclude this blog with a fact that one of my friend told me about starving processes - It is rumored that when the IBM 7094 mainframe at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) was finally shut down in 1973, a very low-priority process was discovered that had been submitted in 1967 and had not yet been run to completion.